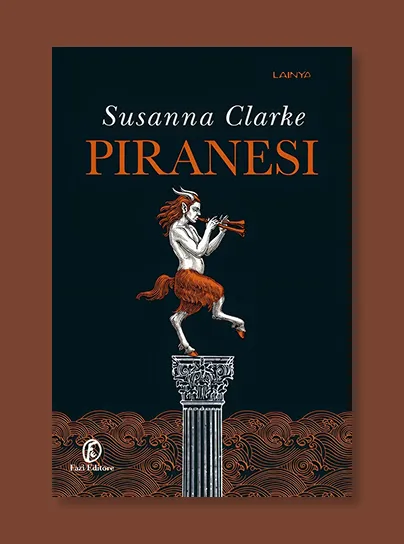

Piranesi

An odd little book.

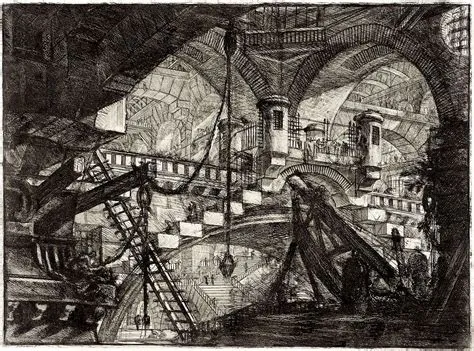

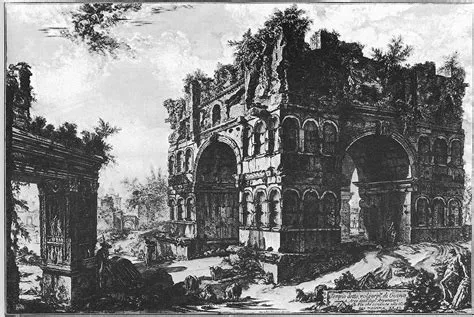

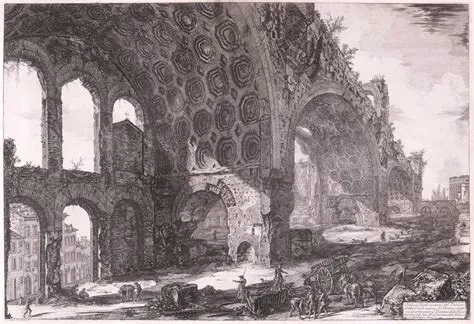

Based on the etchings (some of which are below) of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, an artist who lived in the 18th century, the book is set in a parallel universe comprised of a seemingly infinite number of crumbling halls and vestibules, three layers high, in the four directions.

On every surface of every wall are marble statues, some smaller than life-size, others many meters high. In some of the lower halls, rubble has closed off certain vestibules and the rain has created fresh-water pools. Clouds gather in the higher levels. Periodically, the tide brings swells of ocean water.

I am determined to explore as much of the World as I can in my lifetime. To this end I have travelled as far as the Nine-Hundred-and-Sixtieth Hall to the West, the Eight-Hundred-and-Ninetieth Hall to the North and the Seven-Hundred-and-Sixty-Eighth Hall to the South. I have climbed up to the Upper Halls where Clouds move in slow procession and Statues appear suddenly out of the Mists. I have explored the Drowned Halls where the Dark Waters are carpeted with white water lilies. I have seen the Derelict Halls of the East where Ceilings, Floors – sometimes even Walls! – have collapsed and the dimness is split by shafts of grey Light.

The book is told from the perspective of young man who lives alone in the House, who doesn’t remember who he is or how he got there.

Twice a week, another man, called the Other, comes for short conversations. The Other uses the man of the House, who he calls Piranesi, to gather information for him about the House.

Piranesi’s journal entries are how the story is told and how his reality unravels.

In my mind Raphael is better represented by a statue in an antechamber that lies between the forty-fifth and the sixty-second northern halls. This statue shows a figure walking forward, holding a lantern. It is hard to determine with any certainty the gender of the figure; it is androgynous in appearance.

From the way she (or he) holds up the lantern and peers at whatever is ahead, one gets the sense of a huge darkness surrounding her; above all I get the sense that she is alone, perhaps by choice or perhaps because no one else was courageous enough to follow her into the darkness.

It’s odd because the first half of the book is one journal entry after another of the reality of living alone in the house. The text is full of off-kilter capitalization and I got bored of it, frankly.

It’s not until half way in that the story begins introducing new elements and the style shifts.

Valentine Ketterley, psychologist and anthropologist, has disappeared. The police have made inquiries and discovered that before his disappearance he made some unusual purchases: a gun, an inflatable kayak and a life-jacket – purchases that his friends all agree were completely out of character: he had never shown any inclination to be waterborne before.

We see the entire picture at the end, but the person ends up living fractured within himself.

It’s a melancholy ending that is so subtle that it doesn't really satisfy.

This book won the 2021 Women’s Prize for fiction (Women's Prize?) but would have been better as a graphic novel.

Recommended for people with a very good imagination.